Will Jackson-Moore

Global Private Equity, Real Assets, and Sovereign Funds Leader

Tarek Shoukri

Global Private Equity, and Sovereign Funds Director

Sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) face a growing challenge in generating wealth for future generations in a world careering towards catastrophic climate change. For every year the world’s economies fail to act materially to restrict global warming to two degrees, the need for drastic action becomes more urgent. According to PwC’s Low Carbon Economy Index, at current rates, the global carbon budget for two degrees will run out in 2036.1

The urgency of the problem means multiple sectors are vulnerable to disruption – either from climate change itself, or from increasing efforts to limit climate change, including policy, technology and market measures, together known as “climate transition risks”. Climate change may also create so-called stranded assets. Globally, these include fossil fuel reserves, enterprises in carbon-intensive industries, but local stranded assets might also include companies in sectors that will no longer be viable investment opportunities due to changing weather patterns, such as tourism or agriculture in certain areas.

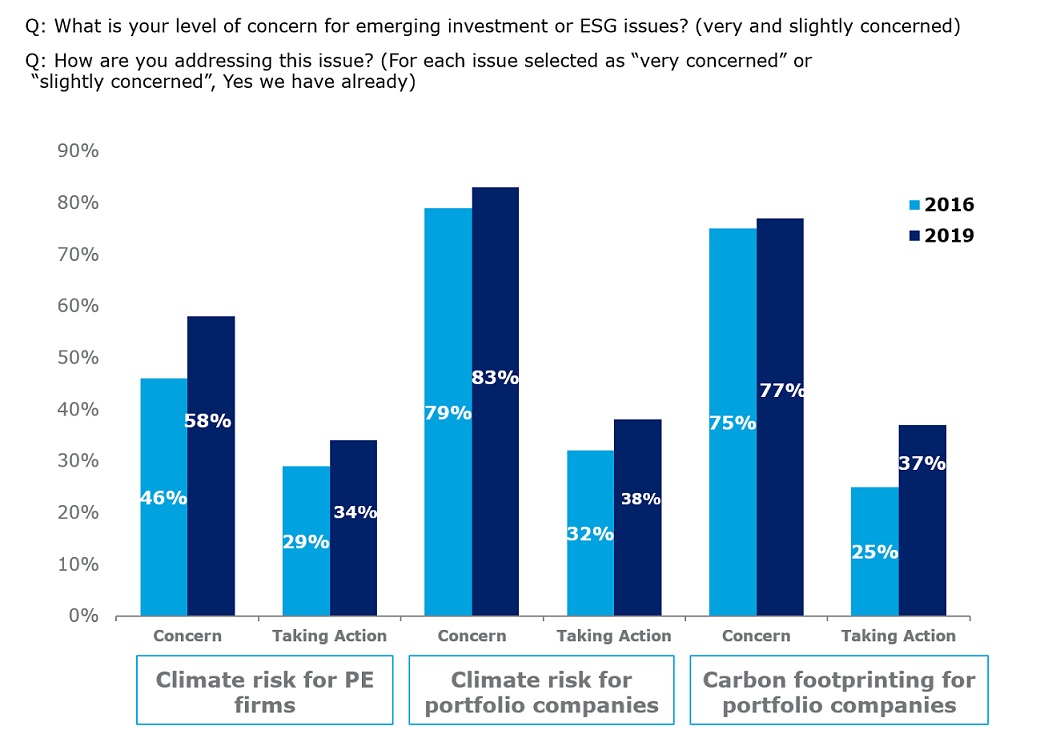

Chart 1.1: Climate Risk Affects Responsible Investmentmate risk affects responsible investment

Source: PwC PE Responsible Investment Survey 2016 & 2019

Base: All respondents 2019 (162), 2016 (111)

For SWFs, particularly those whose wealth derives from commodities, that generate returns from investments in fossil fuels and carbon-intensive industries, this situation presents a potential double (or triple) whammy. Consequently, some are acting to reduce the impact of a move to a low-carbon economy on their portfolios. For example, Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM), which manages Norway’s $1 trillion Government Pension Fund Global, the world’s largest SWF, recently announced that it would phase out oil exploration from its investment universe in an effort to diversify its exposure to oil and gas.2 Similarly, the New Zealand Superannuation Fund (NZ Super) aims to significantly reduce its carbon emission intensity and exposure to carbon reserves by 2020 in an effort to boost its resilience to climate change.3 Around 40% of NZ Super’s portfolio is now “low-carbon”.

While there are genuinely financial reasons for SWFs adapting their portfolios to the results of climate change, as state-owned investors, they are also likely to come under increasing pressure to divest from fossil fuels in the future. These pressures, particularly from young people – the future generations for which many SWFs are meant to be saving – only add more urgency to the need to consider climate risk and develop tangible and effective strategies around this axial phenomenon that will shape their lives.

Consequently, SWFs are developing more nuanced responses than simply moving to low-carbon investing. The Norwegian government has not mandated NBIM to divest completely from integrated energy companies for which oil and gas is currently the main source of revenue, in the hope that these corporations might be in a good position to drive future growth in renewable energy. For example, oil company Shell invests up to $2 billion a year in “cleaner energy solutions”4 – although this is still a minimal investment compared to a $25 billion a year budget to investments in hydrocarbons. Likewise, NZ Super continues to hold some best-in-class companies with high exposure to carbon emissions and reserves because they outperform their peers on climate change issues and demonstrate strong management engagement with the topic.

Climate change is also an opportunity for long-term investors like SWFs, as they can direct their capital into renewable energy projects and other low-carbon technologies to both benefit from the anticipated returns and diversify the source of their wealth. For example, Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala Investment Company, a $225 billion SWF funded by oil revenues, established Masdar Clean Energy, which develops and operates utility-scale renewable energy projects, community grid projects, in 2007. Over the past decade, Masdar has helped the United Arab Emirates to boost solar and wind farm development both at home and abroad. Masdar has a number of solar farms in Spain, and is a major shareholder in the London Array offshore wind farm in the UK, which it also developed.

Boosting returns by improving ESG performance

As well as managing investment risks and protecting future generations from climate change, sustainable investing can help SWFs improve the quality of life for citizens today. A constructive and productive approach is, therefore, not simply about excluding companies that do not confirm to best-practice environmental, social and governance (ESG) practices. Sustainable, long-term investors can also engage with these companies to improve their ESG performance and potentially boost returns.5

Buying businesses with poor ESG records and embedding improved ESG practices within their value creation plans may be key to reconciling three SWF investor demands that look to be incompatible: generating alpha; deploying increasing amounts of capital; investing with impact and high ESG standards.

Research from AllianceBernstein found that, on average, stocks with improvements in ESG ratings outperformed the S&P 500 during the 12 months that followed whereas stocks without improvements in ESG ratings lagged.6 This “Redemption Effect” was particularly pronounced for companies with initially low ESG ratings, suggesting that by engaging with those companies, investors can unlock outsized returns.

Perception v Reality

SWFs also have the ability to drive ESG upgrades in unlisted companies as limited partners (LPs) in private equity funds. For example, a recent PwC survey found 77% of LPs have made a public commitment to include ESG considerations in their investment processes, and 79% of LPs expect general partners (GPs) to report material ESG incidents that arise in their portfolio.7

However, much remains to be done. The Asset Owners Disclosure Project (AODP), a non-profit organisation that scrutinises the responses of the largest institutional investors to climate-related risks and opportunities, ranked the world’s largest asset owners on their success at managing climate risk within their portfolios in 2017. SWFs dominated AODP’s list of “laggards”, although one must bear in mind variations in required disclosure standards, and the diversity of SWFs, before leaping to any general conclusion.8

That said, SWFs are beginning to take action. Last year, six major SWFs established the One Planet Sovereign Wealth Fund Framework, which aims to “accelerate efforts to integrate financial risks and opportunities related to climate change in the management of large, long-term asset pools”.9 Another example is provided by Ireland, which passed a bill that required its sovereign fund to move out of fossil fuels “as soon as practicable”.10

With their profile, their long term nature, ever greater societal focus on “wealth” and what custodians of wealth should be held responsible for, SWFs have much to do – but there is a path forward emerging.

About the authors

Will Jackson-Moore leads PwC's global private equity, real assets and sovereign funds team in London. Will has worked in the deals business for 26 years leading complex border projects for PE and corporate clients. Assignments include due diligence, cost reduction, disposals and restructuring. He was previously based in UAE where he was Managing Partner for PwC in the Middle East Region, prior to that he ran the PwC UK Transactions Services, Private Equity and SWF teams.

Tarek Shoukri is a strategy consultant and mergers & acquisitions advisory practitioner in the global private equity, real assets and sovereign funds team based out of Abu Dhabi. This represents all of PwC’s services to large global investors and their portfolio companies. He leads PwC's global strategy and proposition around sovereign and alternative fund set-up, strategy, governance, and operations advising large GPs, sovereign/pension funds, and cabinet-level government officials.

Notes

1) https://www.pwc.co.uk/services/sustainability-climate-change/insights/low-carbon-economy-index.html

2) https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-47494239

3) https://www.nzsuperfund.co.nz/news-media/nz-super-fund-shifts-passive-equities-low-carbon

4) https://www.shell.com/energy-and-innovation/new-energies.html

5) https://academic.oup.com/rfs/article/28/12/3225/1573572

8) https://aodproject.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/AODP-GLOBAL-INDEX-REPORT-2017_FINAL_VIEW.pdf

10) https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/12/climate/ireland-fossil-fuels-divestment.html