Bernardo Bortolotti, Sovereign Investment Lab, Bocconi University

Alessandro Scortecci, Boston Consulting Group

From Limited Partnerships to Collaborative Investing: Sovereign Wealth Funds’ New Approach to Private Markets

The Big Leap into alternatives

Sovereign wealth funds’ (SWFs) recent step into alternative investments, that large pool of assets stretching from private equity and venture capital to real estate and infrastructure, has been a widely discussed move. Lured by higher and – in some segments – safer yields, a wide range of SWFs tilted their asset allocation away from fixed income towards illiquid investments in private markets. The shift has been dramatic. According to Sovereign Investment Lab research, SWFs have poured $168 billion into alternatives since 2009, reaching a high in 2015 when they allocated $27 billion.1 From a sovereign asset management perspective, allocating a sizable part of the risk budget to private markets makes sense. SWFs’ long investment horizons enable them to put patient capital into early-stage, high-growth companies to generate illiquidity premia over the risk-adjusted returns achieved in public markets. Furthermore, SWFs can attract co-investors into major projects that can potentially boost economic and social development and revenue diversification.

Developing a successful alternatives strategy is, therefore, key for SWFs’ overall performance. However, in practice, the implementation of an ambitious alternatives programme is a daunting challenge, that may have profound implications for the way a SWF operates. Indeed, SWFs have been characterised as an institution with a small staff diversifying a large pool of assets into global public equity markets. However, opportunities in the private equity market often arise by investing early in small firms with high growth potential. Access, capabilities, and timing are fundamental drivers of success in this space.

Traditionally, SWFs, like most institutional investors, built an alternative investment portfolio by committing capital to private-equity-style funds managed externally by general partners (GPs). However, SWFs have increasingly questioned high management fees and the heterogeneity of fund performance, and thus the validity of this investment model. As a result, SWFs have started to develop new ways to tap alternative assets through a combination of direct equity and collaborative investing.

Delegation and co-operation: towards a taxonomy of investment models

Direct equity investment is becoming common practice amongst institutional investors, and a driving force in the disintermediation of financial markets.2 One of the most common types of direct equity arrangement are co-investments. In this arrangement, the investor (limited partner or LP) co-invests alongside the GP in a given target. This arrangement means the LP takes on slightly more risk in return for reduced fees, which mitigates the so-called J-curve effect, in which returns from a private-equity investment may turn negative in the early years before the company matures. Additionally, the LP has more flexibility and control in its portfolio construction and timing, as well as in customising its risk exposures.

Co-investments, however, also have downsides. The GP generally invites co-investors into larger deals, which tend to underperform.3 More importantly, the GP will often give the LP only a relatively short period of time to undertake due diligence. In this situation, the co-investor has limited visibility on the investment and, instead of judging the investment on its merits alone, may be tempted to risk generating lower returns in exchange for the lower fee arrangement.

In spite of these potential risks, many SWFs have embraced co-investment strategies, but they have also sought to improve this model to benefit from additional tactical benefits, such as building stronger relationships with managers, accumulating greater information about investments, and increasing their internal teams’ investment experience. From this perspective, co-investments represent an intermediary step into fully fledged direct equity investment, to carry out alone, or more significantly, in collaboration with partners.

Along this path towards disintermediation and enhanced cooperation, SWFs have teamed up to form investment platforms, usually taking the form of joint ventures focused on specific geographies or sectors. For example, two or more SWFs may commit capital to a closed-end fund investing in the SWF sponsors’ country, as a way to facilitate foreign direct investment (FDI) and commercial links. Notable cases are the many bilateral platforms developed by the Russian Direct Investment Fund, the joint venture recently announced between the China Investment Corporation (CIC) and French bank BNP Paribas with French private equity firm Eurazeo as asset manager, the China-US Industrial Cooperation Partnership sponsored by Goldman Sachs with CIC as anchor investor, or the Italian Cdp Equity’s joint venture with the Qatar Investment Authority. The Vision Fund, the $100 billion platform focused on IT investment sponsored by Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF) managed by Japanese technology investor Softbank, is another example of these new arrangements. However, these investment platforms still involve a significant amount of delegation and intermediation. In most cases, SWFs still need to tap the expertise of GPs, but they are no longer the passive players envisaged in the conventional LP model but the main joint lead/sponsor and anchor investors of the platforms.

Figure 1. Investment models in private markets

|

Cooperation |

||||

|

Low |

Moderate |

High |

||

|

Delegation |

Low |

Direct Solo Investment |

Direct Investment partnerships |

|

|

Moderate |

Pure co-investments |

|||

|

High |

LP model |

Investment platforms |

||

The last stage in the evolution of SWFs’ approach to private markets is fully fledged direct equity investing. In a direct solo investment, the SWF sources and executes the transactions on its own, bypassing the GP and thus pays no fees or carried interest. In a direct investment partnership, the SWF co-invests with a strategic partner (such as a venture-capital fund, or infrastructure or real estate operator) or with other like-minded investors (other SWFs, pension funds or insurance companies), or a combination of both. Direct investment partnerships are thus genuine jointly sponsored deals.

Our taxonomy, shown in Figure 1, is thus complete. In a quest to overcome the conventional LP model, SWFs can choose from several investment strategies in decreasing order of delegation to third-party managers as they move from pure co-investments to investment platforms and partnerships. The transition entails a learning process where SWFs adjust their capabilities and skill sets.

In the old world of private equity, SWFs’ main task as an LP was manager selection. In the game of direct equity investing different competences are needed. An SWF’s internal staff must be trained and experienced in transaction-related activities, including due diligence, operational and monitoring capabilities that are outside the traditional LP skill set. Insourcing the right team is a serious organisational challenge, entailing additional costs and new risks. That is why, as SWFs move away from full delegation models and embark on direct equity investment, they enhance cooperation to pool capabilities and skills with strategic investment partners. In this evolutionary process, collaborative direct equity investing becomes a rational response to disintermediation.

Temasek’s long journey in private markets: a case study

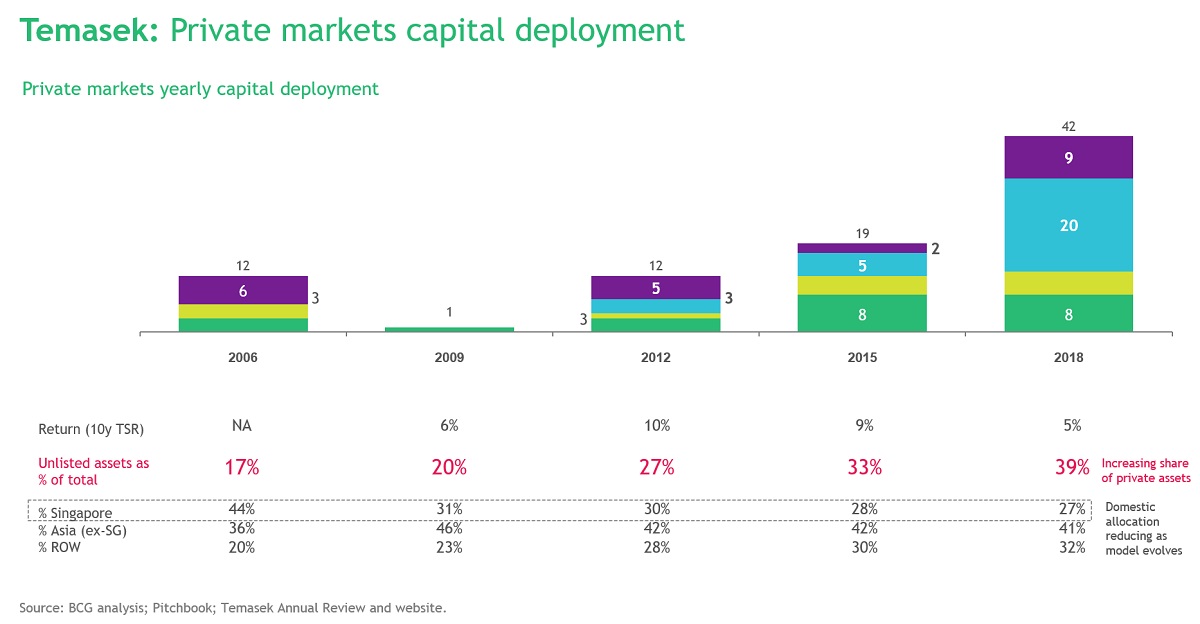

Singapore’s Temasek Holdings has pursued a very effective collaborative investment strategy, advancing along a trajectory that has enabled it to significantly advancing internal capabilities and exposure to private markets.

Before the financial crisis, about 25% of Temasek’s private-market portfolio already consisted of pure co-investments (i.e. deals where Temasek was not the sole or lead partner in the deal, but which had a lead PE fund partner). In these early stages, Temasek’s investments outside Asia accounted for only 20% of their total activity. As the fund's model and risk appetite evolved, Temasek started to become more active in the co-investments and direct investment space (i.e. all private-equity and venture-capital strategies, where Temasek jointly-sponsored or led a deal), using the experience to amplify net returns and drive additional exposure to direct investing. By 2015, Temasek’s co-investment share of its private market portfolio reached over 40%, with its exposure to global markets having increased to 30% of total.

Interestingly enough, in the last three years, we have observed Temasek’s long-term approach to co-investments paying back in terms of access to direct deals. Today Temasek has a strong direct investments programme, with offices in major global financial hubs outside of Asia (New York and London), with direct private-equity and venture-capital investments accounting for 60% of the portfolio.

Temasek has become a successful direct investor through a gradual evolution from being an investor in funds, to partnering in co-investments, and on to direct solo investor, with further levels of sophistication around types of direct investing (mature versus early or growth stage). Having strong LP-GP relationships with major private-equity funds is of critical importance for ongoing co-investment volume and knowledge exposure to emerging areas. At the same time, strategies can gradually evolve from being purely focused on domestic regional investments, to include a broader global reach as the fund strengthens its internal capabilities and expands its reach.

Across multiple co-investment examples, we observe that Temasek’s model and approach is characterised by a relatively high level of maturity, strong experience and a quasi-private-equity fund appetite for direct investments, and a high level of engagement with their co-investment partners.

Temasek’s success can be attributed to three key elements: a strong and experienced team, a forward-thinking approach to investing in advanced or complex technology sectors, and a structured process for undertaking direct investments.

Source: BCG analysis; Temasek Annual Review and website.

An example of Temasek’s approach to successful co-investments is its 2017 investment in The Real Pet Food Company, an Australian supplier of chilled pet food, for US$770 million. Despite Temasek not being the leader in the deal, it had an active role throughout the investment assessment process, developing their independent due diligence on the asset and forming their own opinion on the attractiveness of the investment. Post-acquisition, Temasek is actively engaged with the other partners in the deal to help drive the asset’s North American and Chinese market expansion.

Challenges ahead

SWFs’ journey in private markets is certainly not a linear process of disintermediation. Rather, it is a transition mostly driven by testing different models and adapting and optimising investment strategies along the way. We are not claiming that collaborative direct equity investment are the ultimate, one-size-fits-all investment model for all SWFs. In all likelihood, funds will diversify their investment strategies, maintaining sizable allocations to more conventional limited partnerships with private equity funds. However, a visible trend appears to be unfolding, and the emerging strategies adopted by SWFs including insourcing, learning, branching abroad, and teaming up are all broadly consistent with the objective of getting a better understanding of investments in private markets.

In the bumpy road towards direct equity investing, SWFs will face common challenges with other institutional investors. Overstretched valuations in most segments of the market and intense competition for assets driven by the recent trend of mega fundraising will make it difficult to thrive in this compelling environment.

SWFs, however, will be tested also their governance. Financial intermediaries such as private-equity funds are costly, but also a reassuring presence for both targets and recipient countries, as they can provide a shield from political interference. Commercial objectives and financial returns are in the DNA of private equity firms, and SWFs role as LPs signaled a credible commitment to passivity. As SWFs shift to direct equity, politically motivated investments become an issue abroad and at home. Indeed, SWF as large, direct shareholders in firms will be called to take a more active stance than they have displayed in the past, and this may raise political concerns. The presence of highly skilled private investment partners mitigate the risk, but still SWFs will have to adapt their upstream governance systems vis-à-vis their sponsoring governments to ensure managerial independence while keeping accountability.

In this respect, an interesting development is taking place in Norway, where the government is considering an expert committee proposal to take the $1 trillion Government Pension Fund Global out of the central bank and into its own independent organization. A reserve fund would naturally be housed in the central bank and focus on public assets, while an endowment could have greater independence and delve more into infrastructure and property, as well as other private and less liquid assets. In a recent Financial Times interview, Yngve Slyngstad, the CEO of Norges Bank Investment Management, which manages the fund, claimed that “the central bank has been clear that this is a question of investment strategy and not a question of organisation. It is a question of how we want to think about the fund in a bigger context. That is why this decision is the most important for the last 20 years for the fund.”

SWFs – small and large – are bound to take important decisions. This short article has tried to provide a roadmap and to evaluate some key tradeoffs, but more research is needed to assess and benchmark the performance of the alternative investment models in the direct equity space, taking into account the unique characteristics of SWF as financial institutions.

About the authors

Bernardo Bortolotti is professor in economics at the University of Turin and director of the Sovereign Investment Lab at the Paolo Baffi Center of Central Banking and Financial Regulation at Bocconi University in Milan. His research focuses on the complex relationships between state and markets, with special emphasis on state ownership of firms, regulation, and corporate governance. He is one the leading experts in privatization, state-assets management and divestiture, and sovereign wealth funds. His work appeared in major academic journals and he has published two books with Oxford University Press.

Alessandro Scortecci is a principal with The Boston Consulting Group (BCG). He is a core member of BCG’s Sovereign Wealth Fund practices in the Middle East with a focus on portfolio value creation and digital. Alessandro has worked on multiple large scale strategy and implementation assignments, for large conglomerates, sovereign wealth funds and pension funds, covering investment strategy, portfolio strategy, operating model, organization and governance design

The Sovereign Investment Lab is sponsored by:

Notes

1) Bortolotti, B., Massi, M. Coming of Age: The Evolution of Global SWF Equity Investment, in IFSWF Annual Review, 2017.

2) Fang, Lily H. and Ivashina, Victoria and Lerner, Josh, The Disintermediation of Financial Markets: Direct Investing in Private Equity, Journal of Financial Economics (JFE), 116 (1), 160-178, 2015

3) Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Phalippou, L., & Gottschalg, O., Giants at the Gate: Investment Returns and Diseconomies of Scale in Private Equity Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 50(3), 377-411, 2015