In 2018, sovereign wealth funds continued to invest more in growth-capital financing for startups in disruptive industries. Although SWFs are traditionally conservative investors, some have been keen to finance companies in the early stages of capital raising. Indeed, our data suggests that SWFs are interested in supporting companies through their early-stage and growth-capital phases1. In 2018, SWFs completed 27 transactions at growth-capital stage, up from 19 the previous year, and they doubled their commitments at an early stage with 19 deals versus 9 in 2017.

This interest in early-stage companies doesn’t mean, however, that SWFs are abandoning more mature companies. In 2018, SWF investment in later-stage tech companies was 14 times higher than in 2017, with 14 deals concluded at Series E and F rounds versus only one. These later-stage investments were mainly in the US (10 transactions), with three deals in China and one in India. One example was agritech company Indigo Agriculture, which closed a $250 million series E funding round to finance the launch of Indigo Marketplace™, a digital platform for buying and selling grain. Two mid-sized SWFs participated in this round – the Alaska Permanent Fund Corporation (APFC) and the Investment Corporation of Dubai – which was in the sweet spot for their $50-$100 million cheque size.

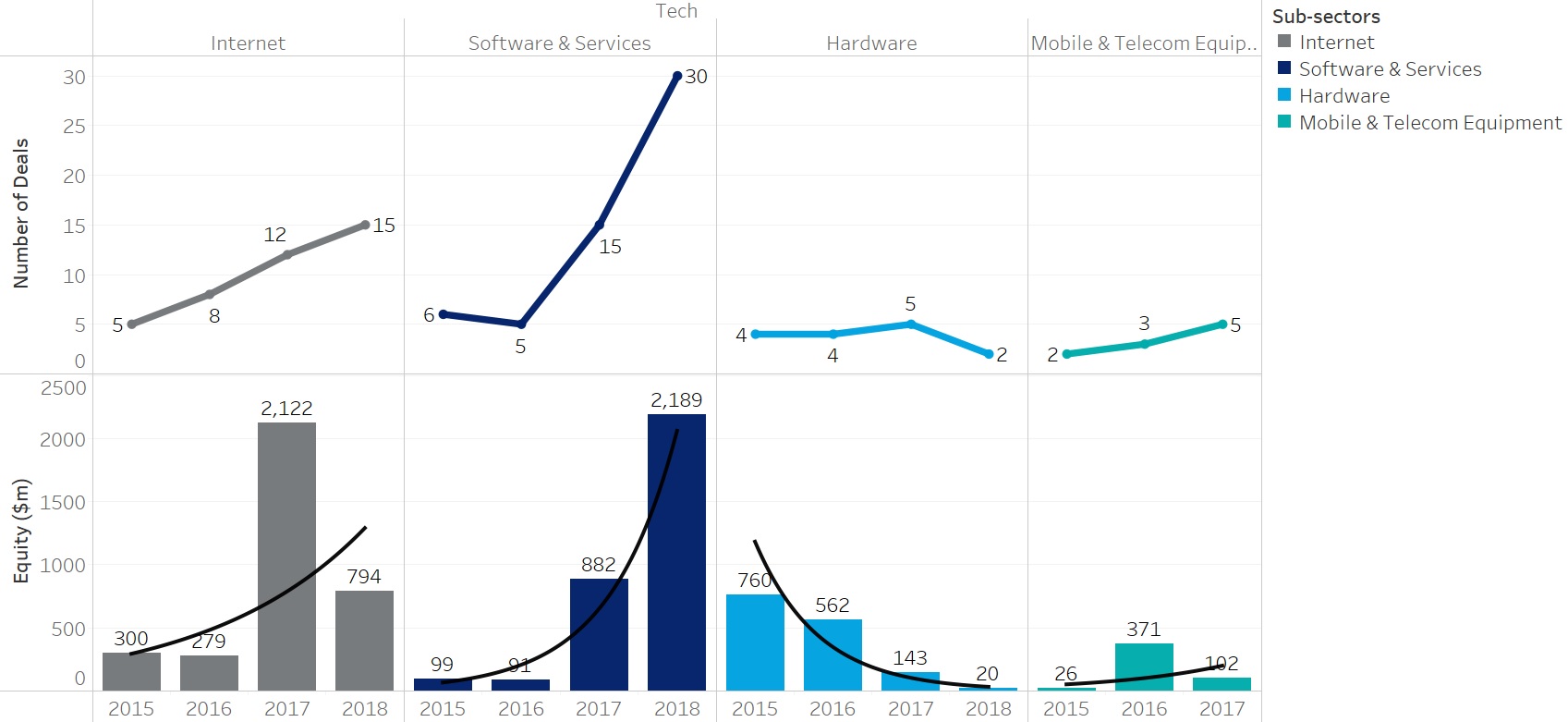

Chart 2.1. SWF investments at different stages of venture financing: 2015-2018

Source: IFSWF Database

In the technology sector, SWFs seem to favour internet-based companies providing services from door-to-door delivery such as Doordash – which raised $535 million from giants such as Singapore’s GIC, SoftBank Group, Sequoia Capital, and the Wellcome Trust – to transport booking platforms such as GoEuro, that raised $150 million with Singaporean state-owned investor Temasek Holdings and Kinnevik, a Swedish investment firm leading the round. The largest investments in software and services include, Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund allocating $400 million to a Series D round for augmented reality giant Magic Leap, and Temasek’s $250 million acquisition of Israeli cybersecurity services provider Sygnia. By contrast, mobile, telecom equipment, and hardware, which face severe price and regulatory pressures globally, were largely shunned by SWFs.

Chart 2.2 SWF Direct Investments in Technology, by sub-sector.

Source: IFSWF Database

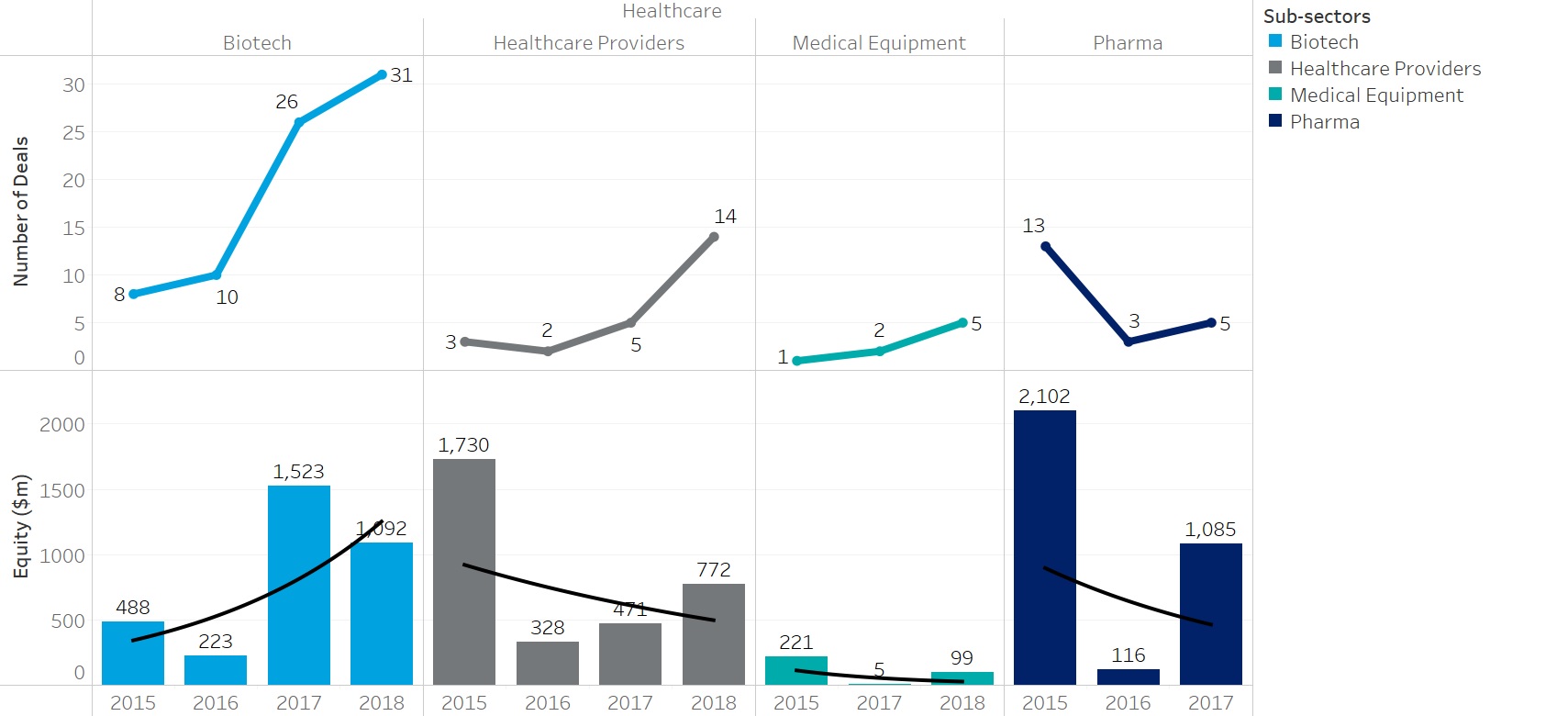

In healthcare, SWFs have been interested in biotech investments, completing 31 transactions in 2018, up from a record high of 26 in 2017. This is three times the number of deals closed in 2015 and 2016. These are also coming in the early stages of capital raising. For example, the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA) participated in the $230 million Series B financing of Gossamer Bio – a company developing novel therapeutic products.

Chart 2.3 SWF Direct Investments in Healthcare, by sub-sector.

Source: IFSWF Database

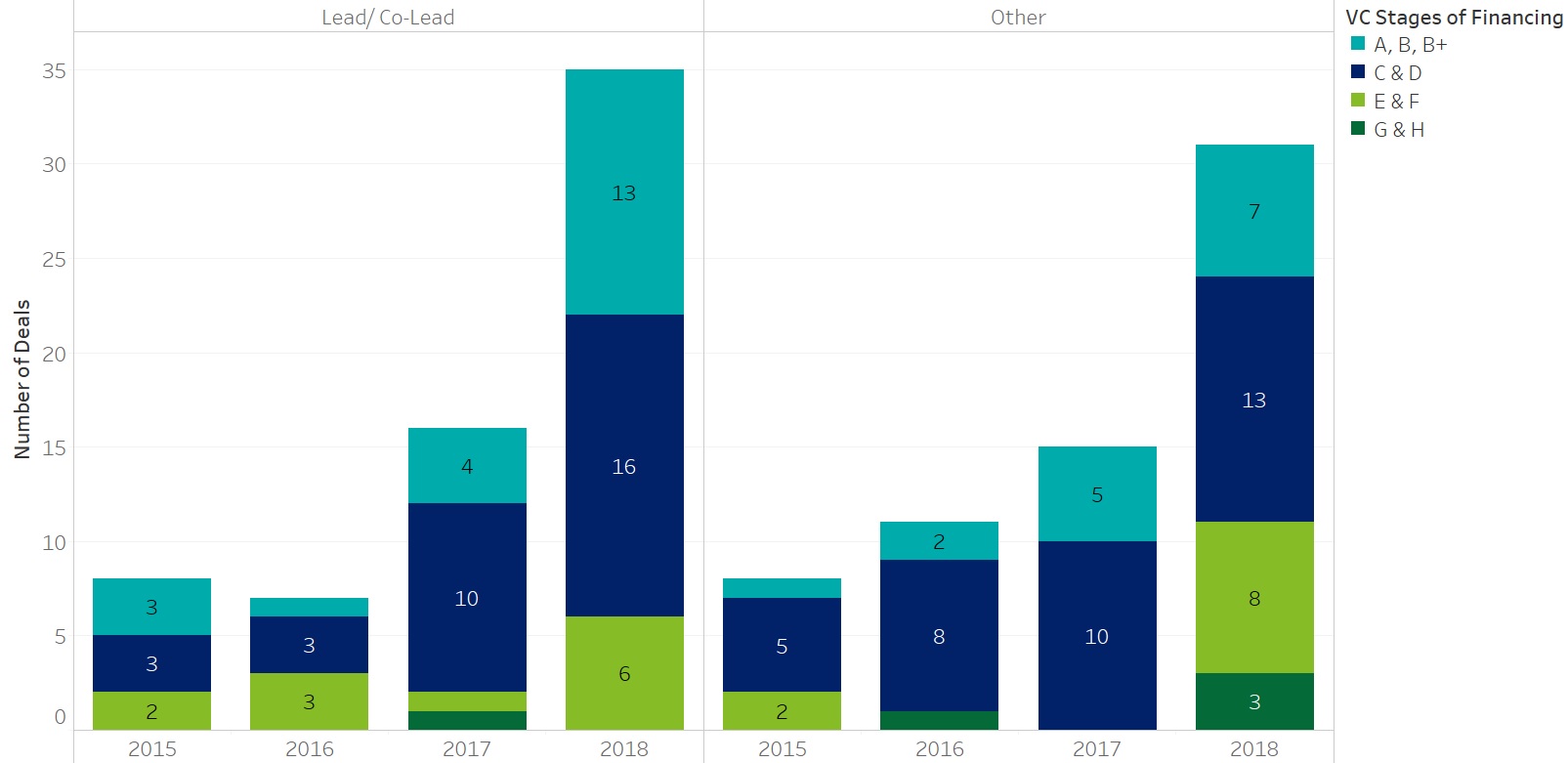

Different Approaches

SWFs gain exposure to disruptive technologies in different ways. SWFs that invest directly in tech companies, including Singapore’s GIC and Temasek, Malaysia’s Khazanah Nasional, Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala Ventures, and the Qatar Investment Authority (QIA), have set up offices or subsidiaries in Silicon Valley. Others have taken a slightly different approach of using dedicated venture capital units such as the Kuwait Investment Authority’s Impulse International. Our data suggests that both these approaches mean these SWFs are prepared to lead a transaction financing an early-stage or growth company with venture capital firms. In fact, in 2018 they led a total of 35 funding rounds more than double the number they did the year before. In 2018, SWFs led 13 early stage, 16 growth and six late stage transactions.

Chart 2.4 SWF Investments as a lead by stage of financing

Source: IFSWF Database

Some SWFs developed long-term relationships with venture capital firms, which help them source co-investments in innovative sectors. According to our data, co-investments with venture capital firms have almost tripled over the last three years, going up from 26 in 2015 to 67 closed in 2018. Australia’s Future Fund, for example, has a $2 billion venture-capital programme, and it often co-invests with Californian venture firms such as New Enterprise Associates (NEA) or Lightspeed Venture Partners.

Additionally, some domestic, strategic SWFs, sees early stage investments as a way to support economic activity and job creation, while generating commercial returns. The Ireland Strategic Investment Fund (ISIF) is perhaps one of the most successful, having contributed to the recovery of the Irish economy since the global financial crisis. For example, in 2018, with Chinese biotechnology giant WuXi NextCODE, ISIF co-led a $400 million investment in Irish life sciences company Genomics Medicine Ireland (GMI). The investment aimed to help make Ireland an important hub for genomics research and development of new disease treatments and cures. ISIF – which is investing $70 million in the project – and WuXi managed to attract major Silicon Valley investors including: ARCH Venture Partners, Polaris Partners, Yunfeng Capital, Sequoia Capital, and fellow SWF Temasek.

Notes

1) For a classification of venture capital financing, we used the most common grouping: Early stage (series A and B), growth capital (series C and D), late stage (series E and F), pre-IPO (series G and H). Please see National Venture Capital Association accessible at: https://nvca.org/

2) See methodology, Impulse is a fully owned subsidiary of the National Technology Enterprise (NTEC) which is a fully owned subsidiary of Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA).

3) See Future Fund’s website for a list of all investment managers, accessible at: https://www.futurefund.gov.au/investment/how-we-invest/investment-managers